Every Black History Month, we take time to reflect on the people and stories that helped shape who we are today. For us, that includes honoring two remarkable women whose names were given to our Community Centers in Charlottesville and Nelson County. Their lives remind us how local Black history continues to guide and inspire our work.

Mary Williams

Mary Williams as a young woman.

The Mary Williams Community Center in Charlottesville is named after Mary Williams. She grew up in Charlottesville with the dream of becoming a nurse. But because she was Black, she wasn’t allowed to attend nursing school in the city. She had to leave home to earn her degree, and even when she returned as a trained nurse, she still couldn’t find a job in the city. Still, she built a successful career elsewhere and returned to Charlottesville to retire. Only then to discover that many older adults, especially Black older adults, had no safe or welcoming place to gather. The senior center at the Jefferson School was in such poor condition that the Health Department was close to shutting it down.

Mary didn’t stay silent. She joined others in organizing a protest and brought their concerns straight to the City Council. “I had to leave once to get an education, and again to find work,” she said, “but don’t tell me I have to leave my own town again just to go to a senior center.” Her courage helped spark real change.

In 2011, her granddaughter, Michele Gibson, stood with us as we named the center in Mary’s honor. Today, the center is located at JABA’s main offices on Hillsdale Drive. Here, members still carry forward her spirit of strength and community.

Cecilia Epps

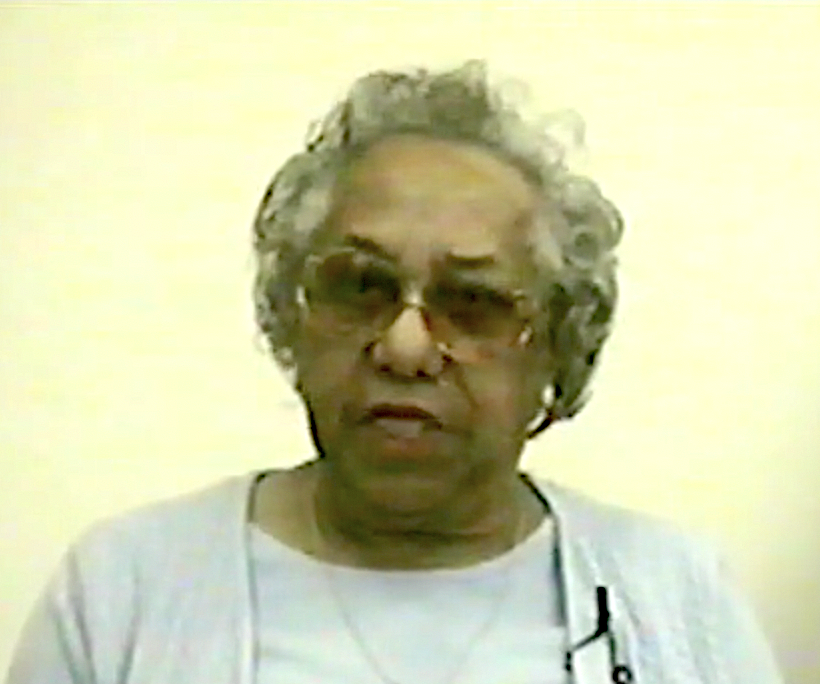

Cecilia Epps.

Cecilia Epps Community Center in Nelson County is named after Cecilia Epps. She spent 38 years working with JABA as an Aging Service Coordinator and Case Manager. In many ways, she was JABA for Nelson County, someone who knew every program, every family, and every need. When she retired, a gym full of people came out to thank her. She also shared her story with the Nelson County African American Oral History Project, describing how she and her husband fought for better schools and helped integrate the county’s education system. Born in 1926, she grew up on a small farm her father bought from a former slave‑owning family. She later built a home of her own and raised six children. Her life was truly remarkable.

The Yancey School & Esmont

In the years after the Civil War, many Black families in Esmont stayed, bought land, opened businesses, and worked together to build a strong, self-sustaining community. Times were hard, and poverty was common, but people supported each other in ways that kept the community resilient.

Black parents, teachers, and leaders even had to take legal action to secure land for a local school. These efforts eventually led to the opening of Esmont High School in 1904. Later, Benjamin F. Yancey Elementary School was established in 1960. When the Albemarle County School Board closed Yancey in 2017, it became the first time in more than a century that Esmont did not have a school. The building was later transformed into a community center and became home to JABA’s Southern Albemarle Community Center. Quickly, members began preserving the memories of the close African American community that shaped Esmont for generations.

In 2024, members created a hand-drawn map of Porters Road from memory. They listed the churches, schools, stores, garages, beauty salons, and gathering places that once lined the road: Thomas Store, Feggans Barber Shop, Esmont Hotel, Cozy Corner, Paige’s Garage, the Cary Sawmill, and more. As one member, Karl Bolden, said, “This one road supported itself. If somebody needed help, somebody helped them. We all supported each other.”

Today, members say Esmont doesn’t feel as close as it once did. New people are moving in without knowing the area’s history, and many who remember the old days are now older adults. Still, as a member and educator, Graham Paige reminds us, “This is a thriving community with a rich history.” He hopes the Yancey Community Center will help protect that legacy and keep it alive for future generations.

Burley High School & Vinegar Hill

Members of the Mary Williams Center also share memories of Jackson P. Burley High School, the segregated school many of them attended. Jackson P. Burley, a respected educator and businessman, sold 17 acres of his own land so the school could be built. It opened in 1951 and graduated its last class in 1967, eight years after integration began. The school later became a middle school. Members often recall the famous Burley Band that lit up local parades and the undefeated 1956 Burley Bears football team, featured in the documentary Color Line of Scrimmage by filmmaker Lorenzo Dickerson. They also remember the Monument Wall added in 2018 to honor that history.

Years ago, members watched another of Dickerson’s films, Raised/Razed, about the vibrant Black neighborhood of Vinegar Hill and how it was destroyed in 1964 because of Urban Renewal policy. Members continue to share their memories of that time, helping keep those stories alive for all of us.